“Coalfire's crisis was seemingly caused by a breakdown in communication and relationship between Iowa state officials, county authorities, and Coalfire themselves; resulting in two infosec pros being treated as pawns in a political chess match."

Malicious actors in the cyberverse don’t exactly play by the rules. Because of this, many companies who value their security fight back by hiring offensive security firms who simulate attack scenarios that an adversary may attempt, adhering to a “takes-one-to-know-one” philosophy.

These simulated attacks, where cyber professionals are tasked to break into systems and locations within agreed-upon boundaries, employ the same TTPs (tools, techniques and procedures) which real-world attackers may use. This is commonly undertaken as part of a penetration test (aka. pentest) or Red Team engagement.

For these tests to be truly effective and indicative of a realistic attack, most staff should not have any idea that anything out of the ordinary is happening; the engagement should be a secret, restricted to only those “in-the-know”. This means the ones hired to execute said engagements run a very real risk of being caught by people who know nothing of the exercise being deployed.

This very situation happened recently, and the repercussions are echoing the world over like a shotgun blast in the Grand Canyon.

Dallas, Iowa County Courthouse, September 11, 2019 - Night

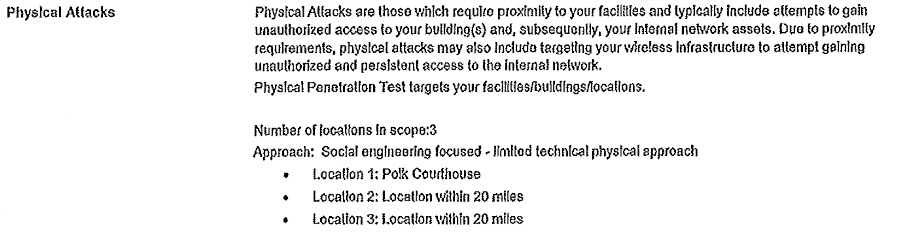

In case you are unaware, cyber security firm Coalfire were hired recently by the state of Iowa to test the digital and physical security of its court systems. Coalfire assigned Justin Wynn and Gary Demercurio, both veterans and respected players in their field, to perform a penetration test which included physical entry.

The two were able to physically slip into the courthouse on the night of September 11, 2019, in an attempt to access network equipment. According to the affidavits, after they found the courthouse door open they closed and locked it and purposefully tripped the alarm to test law enforcement's response time. Apparently when the cops arrived, there should have been no issues, as the team explained what they were doing and presented an engagement letter and proper credentials.

However, both were arrested by county sheriff Chad Leonard on the charges of third-degree burglary and possession of burglary tools when he arrived at the scene, despite being put in contact with a state official who said the men should be set free.

The charges against Justin Wynn and Gary DeMercurio have since been reduced from felony accusations of Burglary in the third-degree and possession of burglary tools to criminal trespass. The pair pleaded not guilty to the reduced charges and demanded a jury trial.

This arrest and all of its subsequent press coverage has added shovelfuls of rhetoric to an already heaping political shitpile that goes far further back than the actual incident. It is now public knowledge that the Iowa state judiciary and the county sheriffs are in a power struggle unrelated to the test, in which certain county authorities have felt slighted by the Iowa Judicial Branch, and the bitterness seems to have contributed to the decision to cuff and charge the pair.

Court officials in central Iowa say they're behind the hiring of two men who were arrested after breaking into the Dallas County Courthouse. In fact, Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady publicly apologized, saying the episode diminished “public trust and confidence in the court system,” adding, “In our efforts to protect Iowans from cyber attacks, mistakes were made.”

Additionally senators are getting involved, calling for an oversight committee to investigate if state court administrators "did not intend, or anticipate, those efforts to include the forced entry into a building."

It's clear Dallas County Sheriff Chad Leonard has taken exception to the situation, and if the state department were trying to catch the county department by surprise, Leonard may have a case to fight. The sheriff stood his ground and by his decision, saying the state could have caused serious harm because law enforcement wasn’t notified. But this is a matter for state and county, not a third party vendor.

“Drop the charges, purge their records. These men are unsung heroes, not criminals.”

Tom McAndrew, the CEO of Coalfire, pulled no punches with his released assessment of the incident:

“The ongoing situation in Iowa is completely ridiculous, and I hope that the citizens of Iowa continue to push for justice and common sense. Our employees were simply doing the job that Coalfire was hired to do for the Iowa State Judicial Branch… (which) included the testing of the physical security of county courthouses and judicial buildings. It is unacceptable that they are now pawns in the dispute between the state and the county related to governance of the court buildings.

Sheriff Leonard failed to exercise common sense and good judgement and turned this engagement into a political battle between the State and the County. I don’t know why he reacted the way he did. Perhaps he didn’t like being tested without his knowledge or that our team found major security concerns at the facilities he was protecting. I’m embarrassed by the way our employees have been vilified… for doing the job they were paid to do. I’m ashamed that no one has had the courage to step up and do what is right. People appear to be more concerned about their own jobs or the political repercussions.

My concern is that common sense is not prevailing in this case. If what is happening in Iowa begins to happen elsewhere, who will keep those who are supposed to protect citizens honest? This is setting a horrible precedent for the millions of information security professionals who are now wondering if they too may find themselves in jail as criminals simply for doing their job.”

Some heavy stones are lobbed here. And while after reading Mr. McAndrew’s impassioned statement/plea it’s hard not to empathize with him, let’s first look at some of the hard facts by delving a little deeper into the actual engagement contract.

The Actual Contract

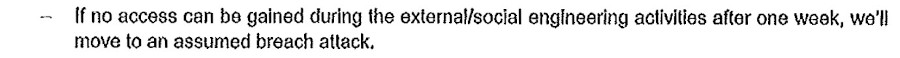

Here’s where the situation gets pretty fucking hazy: Both sides claim that they were in agreement regarding the physical security assessments for the locations included in the contract. Yet, it appears this wasn’t the case, as the state's court administrators were under the impression that the Coalfire team would only try to enter its offices during business hours.

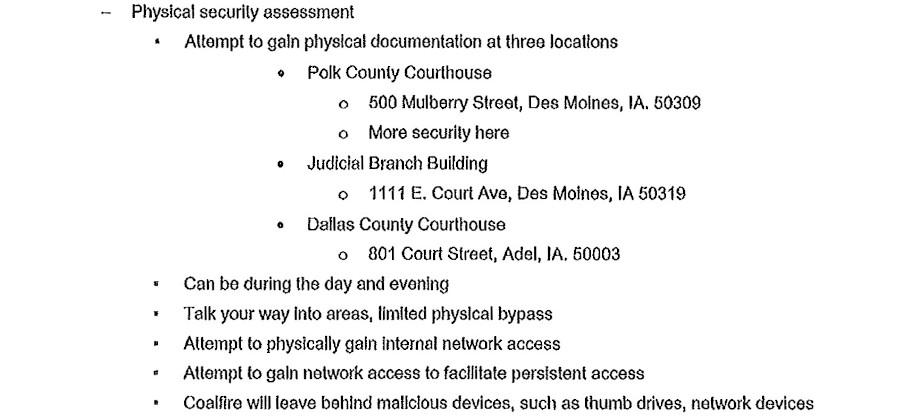

The signed contract3 actually states:

“All testing activities performed by Coalfire Labs are conducted between 6:00AM and 6:00PM Mountain Time, Monday thru Friday, national holidays excepted. Any changes to the scope of the assessment, including version changes, timeline, number of requirements, number of objects to be assessed, or maturity levels assessed will require a change order. ”

Demercurio and Wynn, however, were under the impression they could make their move at any hour, as implied by this section of the contract:

Coalfire said it believed, from the wording of its contract, that its employees were allowed to physically break into the courthouse as part of the IT penetration test the State of Iowa had commissioned.

However, it seems the state court administrators were not aware of this - perhaps due to an oversight on their part - saying they had a different interpretation of the penetration test contract.

This part is definitely questionable. It’s possible Coalfire were not explicit enough, even though the contract states that physical access is in scope. Regardless of whether or not it was in the contract, all of this could have possibly been avoided with more thorough communication and an explicit one page authorization letter covering physical access, signed by both state and county.

Sometimes testers will withhold notifying the client explicitly of the method they will use, because clients will sometimes take precautionary action to stop that attack vector. This is a well known situation and usually fine if the TTPs are in scope on contract.

However, this doesn't come without risk. You have to be absolutely sure the paperwork is solid. And even though the contract states you can rock up and break into buildings, it’s a really good idea to give the client a heads up. Coalfire should perhaps have sent precautionary emails to all those involved, just in case. Of course, there is this caveat from the contract:

“Coalfire and Client shall not send sensitive documents to the other Party via e-mail.”

Coalfire are a well known player in this space but it would appear their legal counsel did not catch these contractual ambiguities. So are Coalfire and their legal counsel to blame for not checking if the state department did indeed have sufficient authority to break into a county building? Or should they have been extra cautious and asked for explicit permission to be signed by the local county building?

I think we can all agree that based on the information made public so far, the testers themselves were not to blame here. If the legal counsel from both sides did not spot these contractual errors, then we can hardly blame two security testers for not catching it either. And while it’s not clear how much was communicated to Iowa state about the TTPs used, as a rule of thumb it’s usually better to be more verbose.

“(The) fight should be with the state administration, not with Coalfire.”

There is definitely some precedent to be set from this debacle. The judicial branch has issued new policies requiring that future security tests are done with the knowledge of local law enforcement.

The outcome of this case will certainly have interesting implications for penetration testing companies, especially those who work with government agencies, both state and local. For one, it’s obvious that this lack of contractual clarity will be a wake up call to companies who undertake adversarial simulation. They would be wise to ensure there’s a clear clause stating that every pentest will include exact details on who is allowed to be where, when they are allowed to be there, and what systems can be probed.

Really the name of the game here is to try and catch the client by surprise, although ideally on-site staff should be able to collar the red team at some point. When things go right, the situation is quickly de-escalated and, more often than not, everyone goes home on good terms with lessons learned.

The key to avoiding these situations is to have clear communication, clear guidelines, and clear plans for what to do in any scenario, not rely on ambiguous contract clauses, although I’m not implying that this is what Coalfire did. Overly cautious is the best course of action in this scenario. Red teams and their clients would be wise to remember this when setting up their own tests.

Ultimately, Coalfire's crisis was caused by a breakdown in communication and relationship between Iowa state officials, county authorities, and Coalfire themselves; resulting in two infosec pros being treated as pawns in a political game of chess.

In this day and age where everyone is quick to shift blame outward by pointing their finger at anyone else other than themselves, and are equally as quick to take sides based on popular opinion over facts, there is more than the fear of becoming a pariah by saying the wrong thing on a social platform. It has now shifted to job security over job quality, where soon no one will perform their job functions properly in fear of being chastised, fired, thrown under the bus or... arrested. And that is a sad, sad state of affairs, indeed. Let’s stamp out the coals to that fire.

References and Additional Readings

1) Press coverage of the incident:- 'Completely ridiculous': CEO of cybersecurity company contracted by judicial branch admonishes handling of employees' arrests

- Remember that security probe that ended with a sheriff cuffing the pen testers? The contract is now public so you can decide who screwed up

- State Court Administration Statement

- Colorado CEO Wants Charges Against Cybersecurity Employees Dropped In Iowa

- Communication, communication – and politics: Iowa saga of cuffed infosec pros reveals pentest pitfalls

- State employees authorized courthouse 'penetration,' urged sheriff not to make burglary arrests, records show